You are viewing

1 of your 3 free articles

Addressing bias when viewing player potential in girls’ football

David Pears and Mike Nolan explain Bedfordshire ETC’s approach to talent ID, ensuring they do all they can to challenge their biases

It is impossible not to have bias(es) when considering player ability, and more so when selecting players for squads.

The NeuroLeadership Institute states, “If you have a brain, you have bias”. Our biases serve a purpose in life. They allow us to use prior knowledge and experiences to inform our decisions and actions. However, while they can add expediency to decision making (heuristics) they can lead to us giving unfair weight or preference to certain player characteristics that may belie player potential.

It is important to make the distinction at this point between talent and potential. In young players, we can only see potential to become talented. Talent is the outcome of the talent development process that takes place as players age and grow. What we see today is potential. We are trying to make a prediction. Our contention is the more information we have about a player and the factors that affect player development, then the better that prediction might be.

When we use the term potential, it reminds us to cast our minds forwards, and it reminds us to judge performance based on a more even playing field by mediating for factors that can confound that judgement.

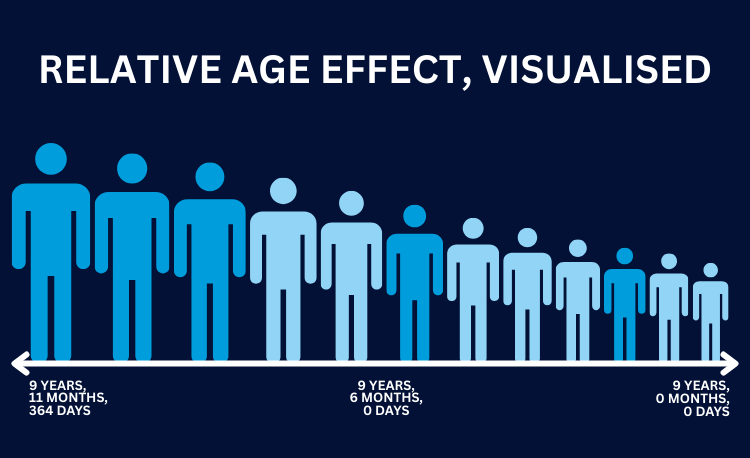

One of the factors we need to consider is relative age effect (RAE). Relative age refers to the subtle chronological age discrepancies between individuals within annually age-grouped cohorts. Football is organised along these annual age bands with the ‘effect’ being potential advantages relating to participation and performance for players born earlier compared to those born later in the age bands.

Research suggests that this bias is cross-cultural and depends on age group cut off dates. For example, the cutoff date in England is 31st August. Therefore, there is a bias towards players born between September and December. In Sweden, however, the cutoff date is December 31st, and the bias is towards players born between January and April.

While there are other effects, the most noticeable is the physical effect. Musch and Grondin (2001) cited physical development as being a major contributor to RAE.

The effect(s) work like this. Early-born performers are more likely to be identified as talented and to be exposed to a higher level of coaching than their late born counterparts. This can lead to recruitment into talent development environments such as ETCs (Emerging Talent Centres). There is also evidence of dropout/self-elimination of later born children.

Apart from the physical effect, Hancock et al. (2013) explained other effects which largely follow on from the physical effect. The Matthew Effect – this is where individuals begin with advantages that their peers do not have, and that those advantages persist over time. Even at the earliest stages of sport involvement this can lead parents to enrol their child in programmes as they perceive the child to be ‘talented.’ This is an ‘enrolment bias.’

The second effect they explain is the ’self-fulfilling prophecy’. The child is judged to be better, they are recruited, often earlier, and receive the best coaching and ultimately end up being better, but mainly due to the opportunities afforded them rather than initial potential.

The third effect, The Pygmalion Effect, refers to the perception that the greater the expectation placed on an individual, the greater the result that individual will reach. Again, if a child is judged to be better the belief of the adults (family, school, coaches) around them is affected and expectations are raised.

Another effect is The Galatea Effect and has crossover with the others. Once expectations are placed upon an individual, that individual typically acts congruently with those expectations. The Galatea Effect refer to the players’ later expectations of themselves.

What can we do to try to recognise potential over ‘talent’?

Over a number of years, Bedfordshire Football Association’s ETC and its’ predecessors (Advanced Coaching Centre (ACC), Player Development Centre (PDC)) have developed a multifaceted approach to identifying potential. Rather than basing selection on a direct comparison at a snapshot in time, we try to consider what a players’ potential might be based on additional factors as well as what we see in front of us.

This is due to a desire to offer opportunities to those with the most potential, but we also recognise that we are at a ‘competitive disadvantage’ to ETCs linked to professional clubs who may have more of a pull for players and parents alike.

In the past, this competitive advantage stretched to centres (ACC) not being able to recruit until after others (Regional Talent Centre (RTC)) had completed their selection process. Therefore, we also needed to be better at selecting players and try to recognise potential that others might have missed and from a smaller pool of players.

The diagram above shows the potential differences across a one-year age band. Due to the funding model, FA Emerging Talent Centres operate with two-year age bands (U10, U12, U14 and U16). This can further exacerbate the difference in age between girls in the same squad.

For example, current U10 players can be born on any date between 1st September 2015 and 31st August 2017. The first key role of ETCs is to identify players with potential and players are selected via a trial process. This process needs to consider how to best consider potential.

It is important to note that this process is imperfect and relies on a great deal of subjective decision making but we attempt to reduce this subjectivity with a range of strategies.

What are the elements of our selection process?

Two trials

Selection is based over two trial dates. We do not make a judgement based on one trial. Further dates would be better, but are not practical. We also offer extended trials where appropriate.

We divide the two-year age groups into four groups, and the players perform the trial in six-month age band groups to reduce potential RAE.

Four-corner approach

We use a four-corner approach. RAE will affect the physical corner most, so technical, social, and psychological elements are considered, helping to reduce any physical advantage. The subgroups, adjusted for age, take part in a carousel of four activities that consider each of the four corners as well as a fifth activity; playing in a small- sided game.

The coaches remain at their respective stations, so while they have a subjective view of the selection criteria, it is more consistent across each group than having different coaches assessing the same station. Apart from goalkeepers, we do not recruit to positions. We consider all round football ‘ability.’

Playing age

We consider ‘playing age.’ This is the length of time the player has been involved in organised football. It helps us to judge potential rather than current performance. That’s to say, if two players are ‘equal’ in observed ability but one has a lower playing age, they may have more potential due to accelerated development.

Playing age may be further impacted by playing time. We know that many clubs or teams within clubs do not have a ‘fair game time’ policy. The best players play most of the game, start most of the time and play in their favourite or most effective positions. The lower ability players get less game time but also get game time that is qualitatively different to that of the better players, such as 30 mins when the team is 4-0 up against bottom of the league. Over 25 60-minute games, Player A might have 1500 minutes vs Player B on 300 minutes! Unfortunately, it is difficult to factor in playing time when selecting players as we do not have this information.

Mixed football

This might seem like we are contradicting ourselves, but playing mixed football might mean the player can cope and this might come from being relatively older. We recognise that there is potential bias here. However, we are looking for players with potential to excel, so being able to cope is a good thing. This also applies across the four sub-groups, so potentially one of the younger players could play mixed football and this would be a plus.

ETC background

We also note if the play has an ETC background as this indicates training experiences with higher ability players.

Relative age

We are actively conscious of relative age. A player’s birthdate is discussed when we make selections. We will take a younger player over an older player if there is minor difference or we can ‘see’ more potential. We recognise this as a potential bias towards slightly younger players. Considering relative age is especially important due to working with two-year age bands (U10, U12, U14 and U16).

We consider the idea of early/average/late developers. Every one of us undergoes a maturational journey from conception to adulthood and most people go through all the developmental stages in the same order and at about the same chronological age without any problem. However, some people develop earlier or later than average and this needs to be considered by coaches. Across a two-year age band there can be as much as a 6.5-year skeletal age difference.

Although it is possible to measure maturational state, we do not currently do this. However, we make a judgement based on observation and this can be more ‘accurate’ when we are considering players who are known to us. We recognise this is a) subjective and that b) we might be working with a bias towards late developers. We are also looking at how we might realistically include calculations of maturity status.

Synthesising the information

The last stage is to synthesise all the above to make the best prediction possible with the information we have. It is important to note that the aim is not to exclude more able players who happen to have a Q1 or Q2 birthday but to ensure that younger players with potential are not disadvantaged.

While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions without a rigorous longitudinal study, and in the knowledge that development is often non-linear; it is noteworthy that a number of players we selected at the younger age groups using this process, who had trialled unsuccessfully for clubs/centres with a better ‘draw’, have subsequently been selected by those clubs/centres when older. The attention to RAE gave them an opportunity to develop that they would otherwise have missed.

Case Study - Ella

At trialsElla was a skilful player but was only ranked in the middle of the group of trialists. If we looked at her from the view of playing ability alone at that given point in time, then she may not have been selected.

What else did we consider?

- Ella’s birthdate is 17th July so is born in the fourth quarter of her selection year.

- At the time of her trial, she would have been described as having a slight build.

- Ella had a low playing age.

- She played in a boys’ team and was coping.

- In the social and psychological activities, she showed good social skills and was viewed as intelligent and able to listen and take on information.

Ella was selected and spent years with Bedfordshire FA ACC before moving to an RTC with a WSL club.

Since then, Ella has:

- Been a WSL academy player u21

- Won the FA Youth Cup

- Played for England at u17 and u19 level

Ella is currently playing college soccer in North America.

Newsletter Sign Up

Newsletter Sign Up

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

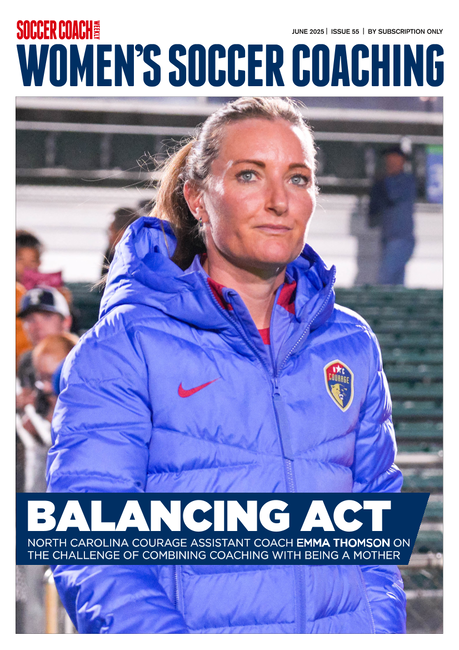

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more confident, 91% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Women's Soccer Coaching offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched Soccer Coach Weekly in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.