The future game: what will an elite player look like?

A research paper by Piggott and Muir in 2023 identified ’the future game’, the concept using the qualities of current senior players to predict future senior players is flawed as the game continues to evolve. While their research took place in the men’s game, Dr James Mayley looks at what this could mean for women’s soccer

To successfully and accurately identify talent, or perhaps more pertinently future talent, in youth football remains a significant challenge at all levels of the game.

Typically, it involves making judgements on players against a pre-determined checklist of desirable skills/attributes deemed important at the time by the scout/organisation. In England, these skills are more often than not grouped to meet the components of the FAs four corner model (namely tactical, technical, physical, psychological and sociological skills). As players become older, these guides will usually become less generalised and eventually take the form of ideal ‘positional profiles’.

Frequently, clubs and scouts will follow this conventional way of doing things without ever questioning its efficacy. Perhaps based on the belief that this is how it has always been done so shouldn’t be questioned. However, a fundamental issue exists with this approach: it uses current performance to assess and make predictions around future performance.

In some ways scouting and talent identification will always be inherently flawed and a number of steps have been taken to address certain issues. There is now a heightened awareness around the non-linearity of development as well as the impact that maturation and relative age effect can have on development and talent identification. However, what is less frequently questioned or discussed is the appropriateness of the criteria against which players are being judged. This has created a phenomenon now known as the ‘future game problem’.

What is the ’future game problem’?

This phenomenon was identified in a research paper by Piggott and Muir in 2023. They argued that given the continuous and dramatic evolution of football over the course of one to two decades, the logic of using the qualities of current senior players to predict future senior players is fundamentally flawed, as in the future the game will pose different challenges and therefore require different skills.

Despite Piggot and Muir’s research taking place in the men’s game, the issue becomes even more prominent in the women’s game, whereby the rate of growth and development currently outstrips that of the men’s game. Put simply, it is likely that the quality, pace and tactics of women’s football in 10-15 years-time will be nearly unrecognisable from the present day.

The future elite female footballer

The women’s game is growing rapidly in popularity and participation rates meaning that the talent pool of potential future players is ever growing. These likely performance gains will be compounded by the level of financial investment in women’s football continuing to increase, opening access to better coaching and sports science support for potential future players. Alongside these physical and skill-based improvements, the globalisation of the sport and ever advancing technology provides increased access to video and data resulting in tactical trends emerging and being adopted at far quicker rates and more globally than at any time in history.

These factors make accurately predicting the skillsets required for an elite female footballer in 10-15 years-time near impossible. The idealised positional profiles will likely evolve and change more than once in that timeframe as the demands placed on female footballers continue to increase. Creating a framework to scout, recruit and develop young female footballers for an unknown future game should therefore be a challenges that all clubs are embracing. Finding an appropriate solution may significantly increase the prospect of developing future talent for the first team or sales, which with the rapid increase in transfer fees within the women game, could provide substantial future return on the investment made into player development.

Demands of the game - current and future

To successfully identify talent for the future game, it is vital to consider the question of what demands of the current game will remain in the future and what new demands may appear? While in some ways this question is near impossible to accurately answer we can probably make a few predictions about what could happen in the future.

Firstly, to date the women’s football has typically copied tactical trends and approaches from men’s football. However, as women’s football continues to mature it is possible, and desirable, that the women’s game will drive its own tactical innovations which are separate to, and different from, men’s football. These changes should focus on finding approaches and styles of play which are more appropriate for, and maximise the strengths of, female players. Therefore, considering what differences exist and how approaches can be adapted for female players may provide a head start to predicting the skillsets needed in the future.

Next, while the game will continue to evolve, Piggott and Muir identified that one thing will remain constant: players will always be presented with, and have to solve, game problems. Indeed, they define talent in football as ‘the emerging ability to find effective solutions to the problems of the game’. While the exact nature of these performance problems will evolve, the principal of facing and overcoming performance problems will always exist.

Therefore, the best players will always be the ones who are best able to adapt to and overcome such challenges.

The nature of the performance problems posed is dependent on the goals, rules and opposition within the sport. While the goals of football will always remain the same (to score while simultaneously preventing the opposition from scoring), the rules and nature of the opposition will continue to change these problems. For example, the introduction of the back pass rule changed the performance problem faced by goalkeepers who now needed to be more efficient with the ball at their feet, while also creating conditions which rewarded high pressing which demanded speed, high fitness levels and increased defensive awareness for forwards within the team.

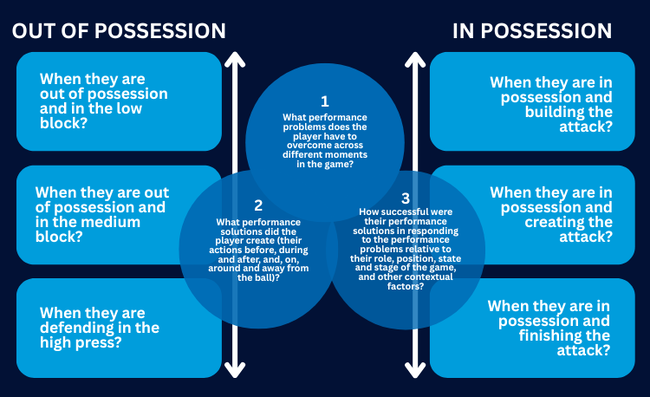

While rules and the nature of players will change, the moments of the game (in possession, out of possession, transition) are likely to remain constant. Therefore, structuring a scouting framework focusing on how players respond to performance problems in these different phases, is likely to yield better future results than a framework structured around the demands of the current game. An example of what this could look like, again taken from the work of Piggott and Muir, is provided in the diagram below.

When using the framework, it is important that observations are made in relation to the players stage of development, level of opposition and state of the game. Moreover, as well as potentially making more accurant prediction of future talent, focussing on solutions players find in all phases of the game may lead to more in-depth reports and observations, further improving the scouting process. For example, it forces the scout to continue to watch a centre back (e.g. their concentration, positioning, communication) even when the ball is in the finish the attack phase and the player is not directly involved.

Finally, it is important to note that no framework will ever be perfect. The ideas put forward in this article should be considered and adapted to the needs of the scout, coach or club that is applying them. However, given the constant evolution of the game, it is vital that scouting future players moves on from judging them against current profiles of elite players. At present, a framework which considers performance problems in relation to moments of the game provides a viable alternative to this approach.

What is the relative age effect?

The phenomenon whereby children born at the start of the year (or in the UK school year e.g. September) have a relative advantage (e.g. more experience from being older, greater physical development) than those born at the end of the year and are therefore more likely to be selected into performance settings.

Newsletter Sign Up

Newsletter Sign Up

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more confident, 91% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Women's Soccer Coaching makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Women's Soccer Coaching offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched Soccer Coach Weekly in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.